Indigenous knowledge & the "wilderness" myth

By Michael-Shawn Fletcher, Lisa Palmer, Rebecca Hamilton & Wolfram Dressler

According to the Oxford English dictionary, wilderness is defined as:

A wild or uncultivated region or tract of land, uninhabited, or inhabited only by wild animals; “a tract of solitude and savageness”.

Aboriginal people in Australia view wilderness, or what is called “wild country”, as sick land that’s been neglected and not cared for.

This is the opposite of the romantic understanding of wilderness as pristine and healthy – a view which underpins much non-Indigenous conservation effort.

Indigenous people are often now excluded from wilderness areas. Photo credit: Wolfram Dressler.

In a recent paper for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, we demonstrate how many iconic “wilderness” landscapes – such as the Amazon, forests of Southeast Asia and the western deserts of Australia, are actually the product of long-term management and maintenance by Indigenous and local peoples.

But this fact is often overlooked - a problem which lies at the heart of many of the world’s pressing environmental problems. Indigenous and local people are now excluded from many areas deemed “wilderness”, leading to the neglect or erasure of these lands.

“Anthropocene” is the term scientists use to refer to the time period we live in today, marked by the significant and widespread impact of people on Earth’s systems. Recognition of this impact has sparked efforts to preserve and conserve what are believed to be “intact” and “natural” ecosystems.

Yet, the Anthropocene concept has a problem: it is based on a European way of viewing the world. This worldview is blind to the ways Indigenous and local peoples modify and manage landscapes. It is based on the idea that all human activity in these conservation landscapes is negative.

The truth is, most of Earth’s ecosystems have been influenced and shaped by Indigenous peoples for many thousands of years.

The failure of European-based “western” land management and conservation efforts to acknowledge the role of Indigenous and local peoples is reflected in recent scientific attempts to define “wilderness”.

These attempts lay out a strict and narrow set of rules around what “human impact” is, and in so doing, act as gatekeepers for what it is to be human.

The result is a scientific justification for conservation approaches that exclude all human involvement under the pretence of “wilderness protection”. The disregard for the deep human legacy in landscape preservation results in inappropriate management approaches.

For example, fire suppression in landscapes that require burning can have catastrophic impacts, such as biodiversity loss and catastrophic bushfires.

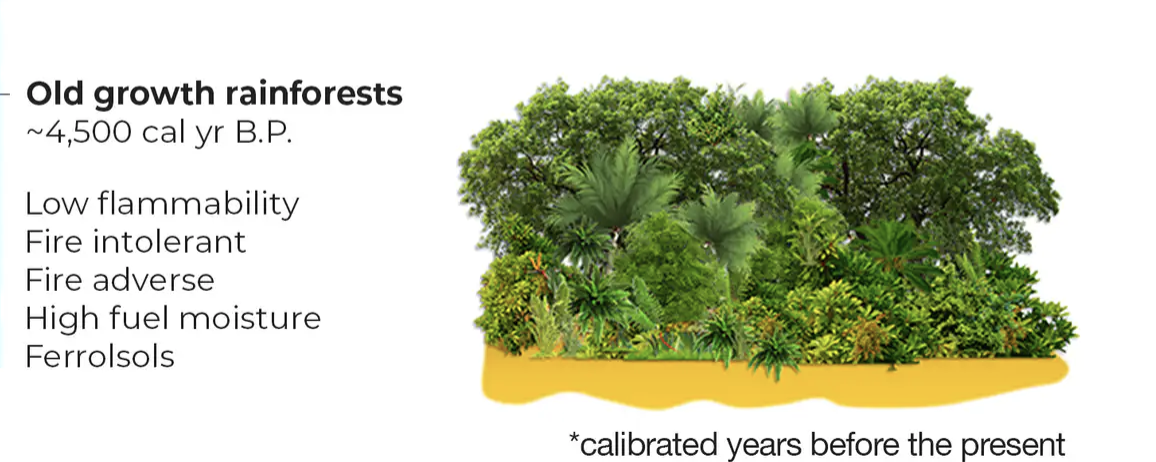

In the Amazon, forest management by Indigenous and local peoples has promoted biodiversity and maintained forest structure for thousands of years.

Areas of the Amazon considered “wilderness” contain domestic plant species, anthropogenic soils and significant earthworks (such as terraces and geoglyphs), revealing a deep human legacy in the Amazon landscape.

Despite playing a key role in maintaining a healthy and diverse Amazon forest system, Indigenous and local peoples struggle constantly against wilderness-inspired conservation agendas that seek to deny them access to their homelands and livelihoods in the forest.

Similarly, the forests of Southeast Asia and the Pacific are some of the most biodiverse regions on Earth. These forests have been managed for thousands of years using rotational agriculture based on small-scale forest clearing, burning and fallowing. Scientific attempts to define the last remaining “wild places” falsely map these areas as wilderness.

Rather than being wild places, agriculture has actively promoted landscape biodiversity across the region, while supporting the lives and livelihoods of tens of millions of Indigenous and local peoples.

In the central deserts of Australia, areas mapped today as “wilderness” are the ancestral homes of many Aboriginal peoples who have actively managed the land for tens of thousands of years.

Removal of Traditional Owners in the 1960s had catastrophic effects on both the people and the land, such as uncontrolled wildfires and biodiversity loss. Unsurprisingly, a return of Aboriginal management to this region has seen a reduction in wildfires, a significant increase in biodiversity and healthier people.

*Michael-Shawn Fletcher, Lisa Palmer & Wolfram Dressler all work at the University of Melbourne. Rebecca Hamilton is from Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

*This article was original published in The Conversation website and is republished under Creative Commons licence.