Grampians Peak Trail - A fieldtrip

Setting out on a four-day hike along the central section of this dramatic new walk, a group of landscape architects and spatial designers encounters a trail design well grounded in place.

Photo Credit: Molly Coulter - Panoramic View - Grampians Peak Trail

Encompassing rocky escarpments and gullies awash in fragrant Thryptomene calycina, the 160-kilometre-long Grampians Peaks Trail (GPT) flows through Gariwerd on Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung Country. The trail designed by McGregor Coxall and Noxon Giffen takes bushwalkers 13 days and 12 nights to traverse – and, since the completion of stage two works for Park Victoria, includes 10 hikers camps.

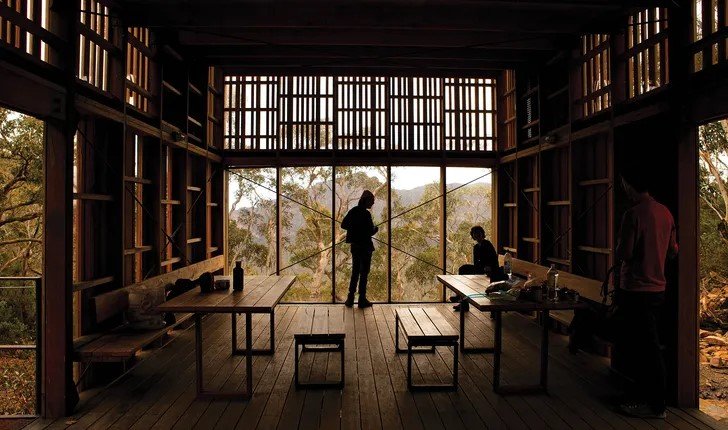

Designed in collaboration with the Barengi Gadjin Land Council, Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation and Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, these hiker camps demonstrate simple yet highly contextual responses that anchor each pause in the journey to its specific, embedded location. Further adding to the intimate sense of place is the relatively small number of tent platforms per camp. These are discreetly placed and vary by site, with communal shelters in some and hearth-like gravel seating in others. The northern section features communal shelters at every campsite, while the central section predominately has seated gathering areas with timber palisade windbreaks. It’s worth noting that specific shelters have been designed for these central section sites, and they have the potential to hold communal shelters in the future. In keeping with the site context and Parks Victoria’s established material choices, the design team has extensively used weathering steel, in addition to timber. Gar campground, for instance, responds to its exposed situation with charred large-format battens, while the more nestled Werdug campsite has sparser, thinner and lighter timbers that break up the shelter’s form among the scraggy surrounds.

Battens and noggins vary in size and type between sites, giving each shelter its own look and feel while maintaining the same fundamentals. Shelter - Grampian Peaks Trail. Photo credit: Molly Coulter.

Between these places of rest, the GPT regularly ascends, descends and ascends again, constantly affirming that “Peaks” is a well-earned part of its moniker. Hikers encounter gravel tracks, in situ masonry steps, and yellow markers that – despite being placed by Parks Victoria – are more suggestions fixed to rocks at intervals. These challenges provide the trail with a grade 4 rating from the Australian Walking Track Grading System, with some portions designated grade 5 (most difficult).

And so it was with trepidation that the five of us began our four-day hike, stepping onto the trail at Barri Yulug on a Friday afternoon. A sixth person had already bailed before we left Melbourne, anticipating the thunderstorms and cooler temperatures we would likely encounter. Having hiked the northern section from Roses Gap Road to Halls Gap a few months prior, our goal this time was to hike four days of the trail’s central section. However, recent flooding south of Yarram caused closures, cutting short the distance before we had even departed.

Native Flora on Grampians Peak Trail. Photo Credit: Molly Coulter.

We dropped our pickup car earlier than planned, next to Yarram Gap Road, then hiked for a few hours, stopping in the sun to chat and catch our breath as we looked out over the giant sandstone slab we’d steadily climbed over beside Lake Bellfield. When I’d been here in the middle of winter, everything was in full bloom, a cacophony of yellows, reds and pinks: bundles of Epacris impressa, the floral emblem of Victoria with its downturned pink flowers; rusty yellow Dillwynia glaberrima, Acacia paradoxa and invasive Acacia longifolia. That Friday, though, it was Xanthorrhoea australis and Banksia ornata, the latter’s flower spikes standing out in their different phases of growth as we gained altitude, sitting down to take breaks on mountainside rocky slabs in an area that was, according to our contour map, aptly named “The Battlements.”

Hikers traverse mountainside rocky slabs, guided by yellow markers that are fixed to rocks at intervals. Photo Credit: Molly Coulter.

Having commenced our hike so late in the day, we reached Duwul (the new stage two hikers’ camp) with the last of the light. We pitched our tents – some of us on granitic sand, others on timber platforms according to preference – and pondered what purpose the steel plates at two corners of the timber tent pads might serve. (They’re for cooking on, we later discovered.)

The next morning, we woke to find the weather had turned from sunny to overcast. We cooked breakfast, marvelled over the toilet’s four USB chargers, set out with our packs – and then, the rain started. Hoping the weather would hold, we made the hour-long hike to the Mount William car park but were disappointed: when we arrived, it was pouring, and the temperature had plummeted. Still, we decided to summit Duwul/Mount William. Saturated and freezing, we did … and found zero-visibility conditions at the peak. We briefly huddled, deciding to bail rather than stick around in the “feels like” temperature of -5 degrees Celsius. Fortunately for our group, the Halls Gap YHA had exactly five places left; we grabbed them, along with an opportunistic hitchhike back to the first car.

After a night of drying off in town, we travelled south to the originally intended destination point at Yarram Gap Road and hiked up to Yarram, mostly packless, and able to move lightly. This hikers’ camp is positioned in a natural amphitheatre, and the shelter is its heart: as in Werdug, where camp platforms are on one side and water tanks and amenities are on the other, you find yourself always coming back to or through it. All spatial designers, we explored, pried, climbed up, and enquired into all the details. One standout was a weathered steel washbasin with a concealed grease trap, a detail that arguably should become standard for water tanks at all national park campsites.

When it comes to design, the GPT opts for simple, highly contextual responses over the increasingly development-minded “experience”-oriented approach that some trails are headed towards. As different as each camp is to the next, all are situated within the GPT rather than upon it. The trail is one well-grounded in place – a journey that asks of us a genuine investment in time with which to engage and embed ourselves in the landscape.

This article was originally published in the May 2023 edition of Landscape Architecture Australia magazine and is shared with the permission of Landscape Australia Magazine, and the Author, Matt Caldar.