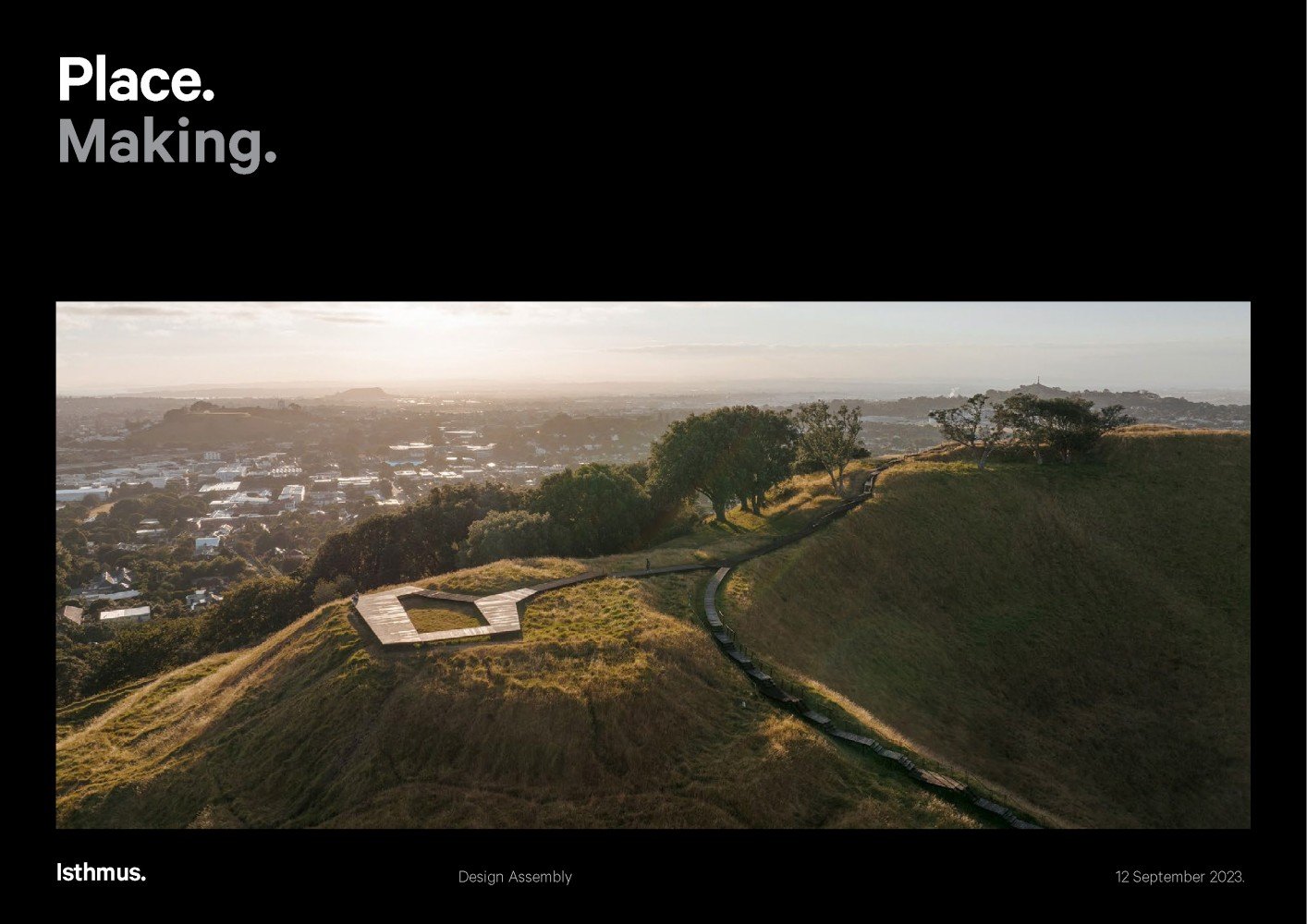

Place. Making.

I recently spoke at the Design Assembly Spring Conversations series alongside Hori Te Ariki Mataki, Richard M. Burson and Carl Pavletich, and convened by Helen Kerr.

The broad theme was Placemaking and my kōrero focused on the importance of understanding place before jumping into solution-making. My talk was somewhat organic in nature, but I thought it worth sharing the bones.

Nik Kneale. Photo Credit: isthmus.

I opened with my pepeha, as I often do. It’s a far deeper and more meaningful introduction than the kiwi “how y’garn, I’m Nik”. It locates me in time and space. In time by acknowledging those who have come before me, and those who are my descendants. In space by acknowledging where my ancestors are from, and by describing my relationship to the place I call home.

I whanau mai ai au, kei raro i te maunga o Te Pōhue,

I was born under Te Pōhue (Sugarloaf, a prominent peak on the Port Hills),

I tipu ai au, ki te taha o te awa o Ōtākaro.

I grew up on the edge of the Ōtākaro Avon River.

I don’t claim these places as mine, I acknowledge them as important features that define the place I call home. The physical features I acknowledge hold spiritual and whakapapa significance to mana whenua, so I also acknowledge my place within their rohe (area).

I tipu ai au kei raro o te mana o Ngāi Tahu o Ngāi Tūāhuriri hoki.

I grew up under the mana of Ngāi Tahu and more specifically Ngāi Tūāhuriri, whose rohe includes Ōtautahi Christchurch.

So that defines me in my place, but I have a beef with the term Placemaking.

The intent is good, the outcomes are good.

Head to https://www.placemaking.nz/ for further information, there’s some great material on there.

But here’s my beef - the term alludes to a place NEEDING TO BE MADE.

Place.Making. Photo Credit: Isthmus.

Places already exist.

They have their own qualities, no two the same. We live, work and play within them, and they’re a product of the layering up of land, people and culture.

They’re part of our identity, sometimes deeply such as mana whenua connection through whakapapa, and sometimes on a shallower level – that classic Christchurch question “what school did you go to?” comes to mind. In fact it came up over drinks before the presentations started. Turns out Hori and I went to the same school at different times, Richard went to school with one of my Isthmus colleagues and Hori and Richard both studied in the building where the event was being held. I’ve always resisted it, but I’m starting to think the question is a legit way to connect here in Christchurch.

In many of our cities and towns, our reasons for being there are often lost over time. Our ancestors chose places to live based on abundance – reading the landscape and locating themselves where they and their communities would have the best opportunities to thrive. Sometimes these were permanent homes, sometimes seasonal. In many places we’ve disconnected ourselves from these reasons for being. Gradual, intergenerational decisions such as industrialization of our water’s edges, the covering over of our productive soils with roads, industry and housing, and turning our backs on our rivers and estuaries – changing these essential life-giving environments and critical lifelines into drains and threats.

As such we are more disconnected from our places, so our work focuses on drawing land, people and culture back together. To do that we read the land and we work with the people. We follow a process that places whanau and whenua at the centre. Regardless of the project, understanding the place – the land, people and culture is #1. This is the strongest foundation for the best outcomes, and frankly it's the only way to create solutions that the community will see them selves in. They see themselves in the solution because they helped create it. Local champions maintain the energy long after the consultants' work is done.

In Invercargill we're reconnecting the city to its people, and to its reason for being: the rich natural environment. We're helping realise the opportunities identified by local champions.

Invercargill Story. Photo Credit: Isthmus.

The streets delivered to date are cleaning the city's water before it hits the estuary, providing play and discovery trails in the urban heart, telling stories of early and ongoing relationships and creating comfortable places for people in streets previously seen as essential for car parking.

City on the Estuary. Photo Credit: Ishtmus.

In the Ōtākaro Avon River Corridor, we're working to understand what the future looks like in this conflicted space - a 63 hectare area following the river from city to sea, with a vision to be an authentic ecosystem - the lungs of the city - but grappling with the recent memory of managed retreat following the Canterbury Earthquakes. Around 10,000 people were directly affected by the process, as in, they needed to leave. Managed retreat at a significant scale in a short timeframe. The effect of that is still felt in the communities left, and in the remaining landscape. The houses and fences have gone, but clues remain everywhere. Taking time to understand has been critical.

Ōtākaro Avon River Corridor. Photo Credit: isthmus.

Principles and key moves have been developed based on the place, its history and the future intentions. They're generated from understanding the place, not copy+pasted from another place. A language of place has developed, and this has become critical to thinking about design at all scales and stages. And we're connecting with community, particularly current and future kaitiaki. They're invested in their place, and they're passionate champions for its future. So in summary, place first, making second. We need to understand where we are, who we are and why we're here in order to fulfil the potential of the place.

Place first. Making second. Photo Credit: isthmus.

This story and photos are shared with the permission of Nik Kneale and Isthmus.